Draft, Asthma Van Visit St. Louis Schools

July 01, 2009

By BLYTHE BERNHARD

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

When it’s hard to breathe, it’s hard to stay in school, play with friends and just be a kid.

A mobile asthma clinic run by St. Louis Children’s Hospital travels to 13 elementary schools around St. Louis to test kids for the lung disorder and check in with those who have already been diagnosed.

At some schools, nearly a quarter of kids are asthmatic. That’s three times higher than the national average, and combined with St. Louis’ ranking as the most dangerous place for people with asthma, you get lots of kids struggling to breathe.

Kids like Tevin Tourville, 13, who often sits on the sidelines when his friends are out playing.

“I can’t do what I want to do,” said Tevin, who likes to play football and run track when his asthma is in check. But when his symptoms act up, “I have to sit down. I can’t play anymore,” he said.

Tevin visited the asthma van recently at his school, Lucas Crossing Elementary in Normandy. There, a nurse reminded Tevin that he can inhale his albuterol and open his airways before exercise to keep him playing longer.

Last year, 727 schoolchildren received asthma treatment through the Healthy Kids program. The new asthma van joins two other roving clinics that test kids’ vision and hearing and offer immunizations for free thanks to various grants.

The van travels to Lucas Crossing more than any other school, since about 200 out of 800 students there are thought to have asthma. All the schools in the program have reported a reduction in absenteeism by an average of 13 percent.

Asthma is generally controllable, but it’s hard to get kids to comply with complicated drug regimens and breathing exercises. The nurses on the van consistently remind the kids about how and when to use their inhalers.

Joan Upperman, a nurse and respiratory specialist who works full time on the van, said the kids inspire her because with “all of their challenges they just keep going.”

Some kids come to the van wheezing and need immediate steroid treatments to reduce inflammation of their air passages. Several said they sometimes feel like they’re going to die.

Kindergartner Anyia Davis said she coughs and loses her breath whenever she smells barbecue smoke.

“When I get sick it makes me more sicker,” said Anyia, 6. “And my heart beats very, very fast.”

Each kid with asthma is seen on the van at least three times during the school year. It helps them recognize their asthma symptoms, manage their medications and reduce school absences, said Lucas Crossing school nurse JoAnn Mills.

“Without it I don’t see how we would have been able to safely manage the illness,” she said.

It’s dangerous not to. Chronic respiratory disease, including asthma, is the fourth-leading cause of death in the St. Louis area. Emergency room doctors say they have seen children in full-blown asthma attacks who have never before been treated.

This year, the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America named the St. Louis region the nation’s worst for asthmatics, based on factors including an above-average death rate from asthma, a lack of smoke-free laws and high pollen counts.

While it’s unclear why asthma is so much more prevalent in St. Louis, there are some known factors starting with nutrition.

A high-fat, high-salt diet can narrow and irritate airways, and studies have linked fast food diets to higher rates of asthma.

Vitamin D deficiencies are also connected to higher rates of allergies and asthma, according to a recent study of schoolchildren in Costa Rica. It’s known that people with darker skin tones have a harder time absorbing the vitamin from sunlight.

Breastfeeding may also play a role, although its connection to asthma has been debated. Some studies have shown that babies who are exclusively breastfed have a lower risk of asthma, while others have failed to find a relationship.

What’s important for parents to remember is to seek medical help for a child who wheezes, coughs at night or routinely sits on the sidelines during physical activities.

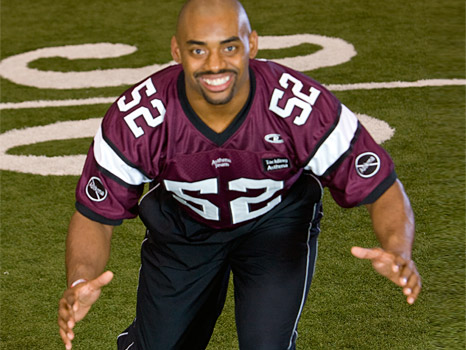

And if they don’t listen to their parents or nurses, they might listen to St. Louis Rams linebacker Chris Draft. Draft first realized he had asthma as a college football player and suffered an attack during the Rams’ training camp in 2007.

Now he calls himself Asthma Man and talks to kids, parents and legislators about his initiative “Tackling Asthma.”

“When you think of someone with asthma, you think of a kid who’s stuck in the corner and can’t do anything,” Draft said. “For me to just say that ’I’m Chris Draft and I have asthma’ already changes the expectations of what the parents and the kids think they can do.”